Calculations Involving Masses – GCSE Chemistry

Introduction

- Mass is a fundamental property of matter, representing the amount of material in an object. Calculations involving mass are essential in physics, chemistry, engineering, and everyday applications. These computations often include:

Basic Mass Measurements

- Determining mass using balances or scales, typically in grams (g) or kilograms (kg).

Molar Mass Calculations

- Relating mass to the number of particles (atoms, molecules) using Avogadro’s number (6.022 × 10²³ mol⁻¹).

Conservation of Mass

- Balancing mass in chemical reactions or physical processes.

These principles form the basis for more advanced topics like Stoichiometry.

Mole Concept

- A Mole (mol) is the standard unit in chemistry for counting tiny particles like atoms, molecules, or ions.

1 mole = 6.022 × 10²³ particles (Avogadro’s number)

Why Use Moles?

- Atoms are too small to count individually (e.g., a drop of water has ~10²¹ molecules!). Moles let us:

1. Counting Particles Easily

- A single atom weighs ~10⁻²³ grams—too small to measure.

- 1 mole = 6.022 × 10²³ particles (Avogadro’s number), allowing us to count atoms by weighing.

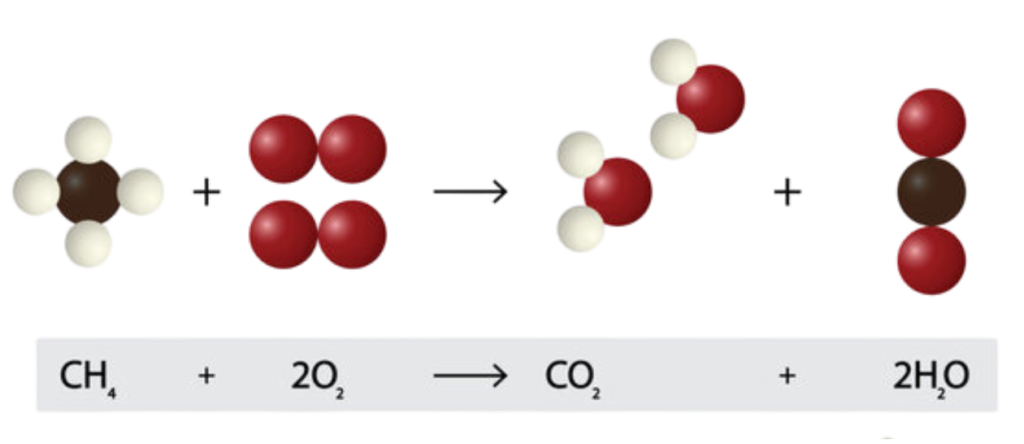

2. Simplifying Chemical Reactions

- Reactions depend on ratios of atoms/molecules, not mass.

Example:

- 2H₂ + O₂ → 2H₂O means 2 molecules of H₂ react with 1 molecule of O₂.

- But in labs, we measure grams, not molecules.

- Moles convert grams → molecules, making reactions practical.

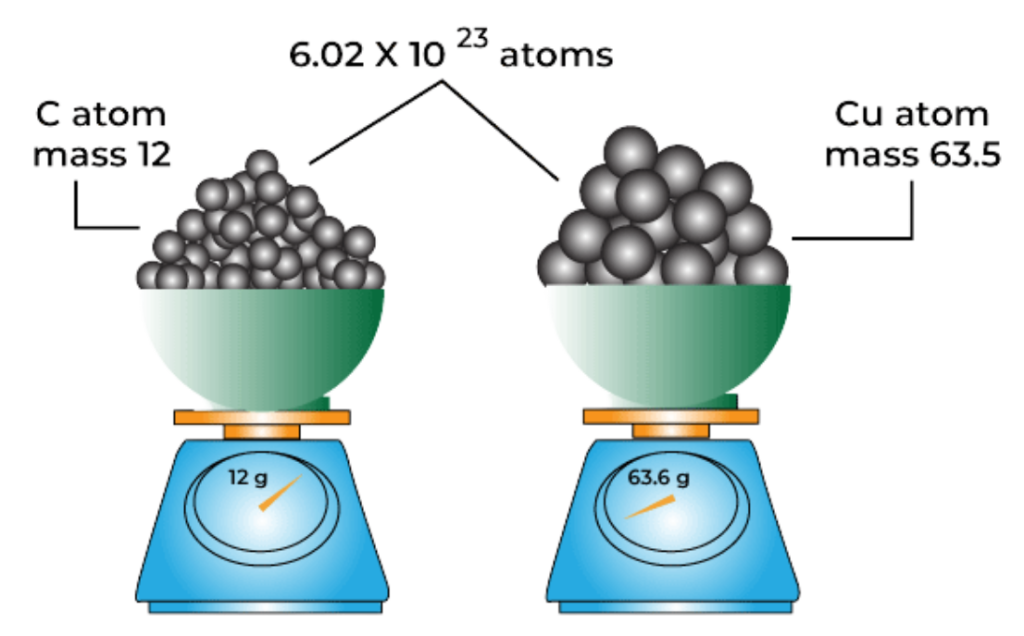

3. Connecting Mass to Number of Particles

- Molar mass (mass of 1 mole) links the periodic table to real-world measurements.

Example:

- Carbon (C) has a molar mass of 12 g/mol.

- So, 12 grams of carbon = 1 mole = 6.022 × 10²³ atoms.

4. Standardizing Measurements

- Allows chemists worldwide to use the same scale (grams → moles → particles).

- Essential for stoichiometry, gas laws, and solution chemistry.

Why It Matters

1. Making the Invisible Visible

- Atoms and molecules are too small to see or count individually, but we need to work with them in labs and factories.

Example:

- A single iron (Fe) atom weighs ~9.3 × 10⁻²³ grams.

- But 1 mole of iron (55.8 g, about a small nail) contains 6.022 × 10²³ atoms—a measurable amount!

2. Essential for Chemical Reactions

- Chemical equations (like recipes) depend on ratios of particles, not mass. Moles make this practical.

Example:

- The reaction 2H₂ + O₂ → 2H₂O requires 2 molecules of H₂ per 1 molecule of O₂.

- But in a lab, you measure grams, not molecules.

- Moles let you mix 2g of H₂ (1 mole) with 32g of O₂ (1 mole) for the perfect burn.

3. Industry & Manufacturing

- From plastics to fertilizers, factories rely on moles for cost control and quality.

Example:

- The Haber process (N₂ + 3H₂ → 2NH₃) uses moles to produce ammonia efficiently.

- Too little hydrogen? Wasted nitrogen. Too much? Explosive risk.

- Moles optimize raw materials and prevent disasters.

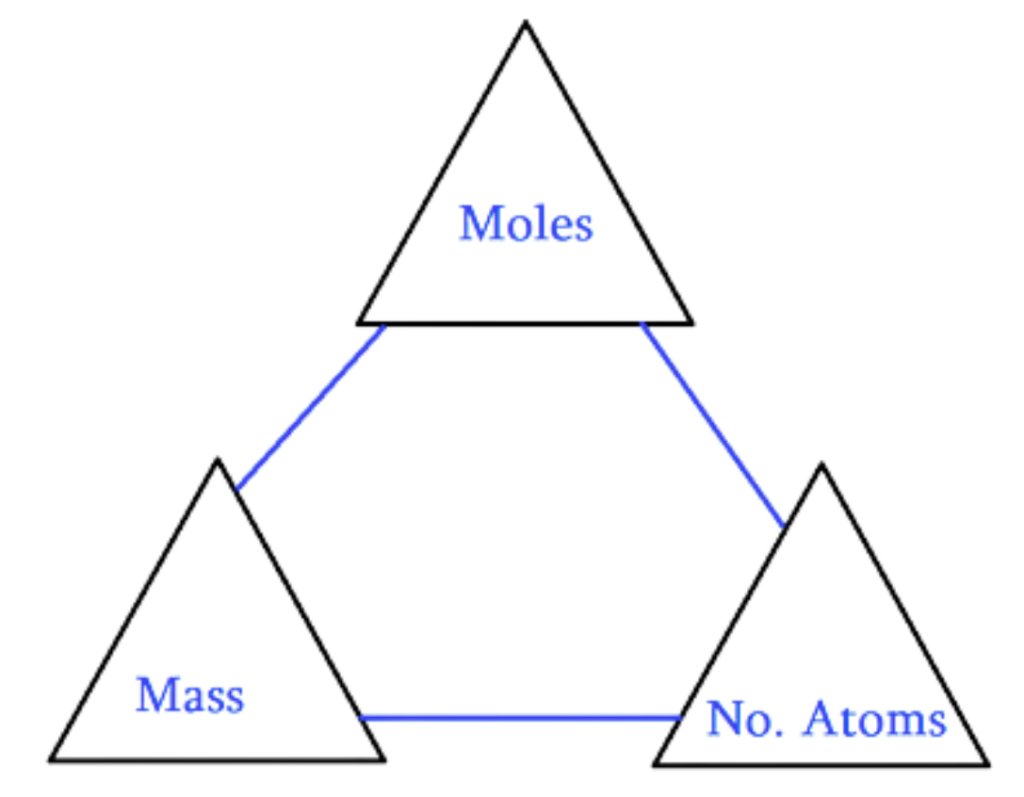

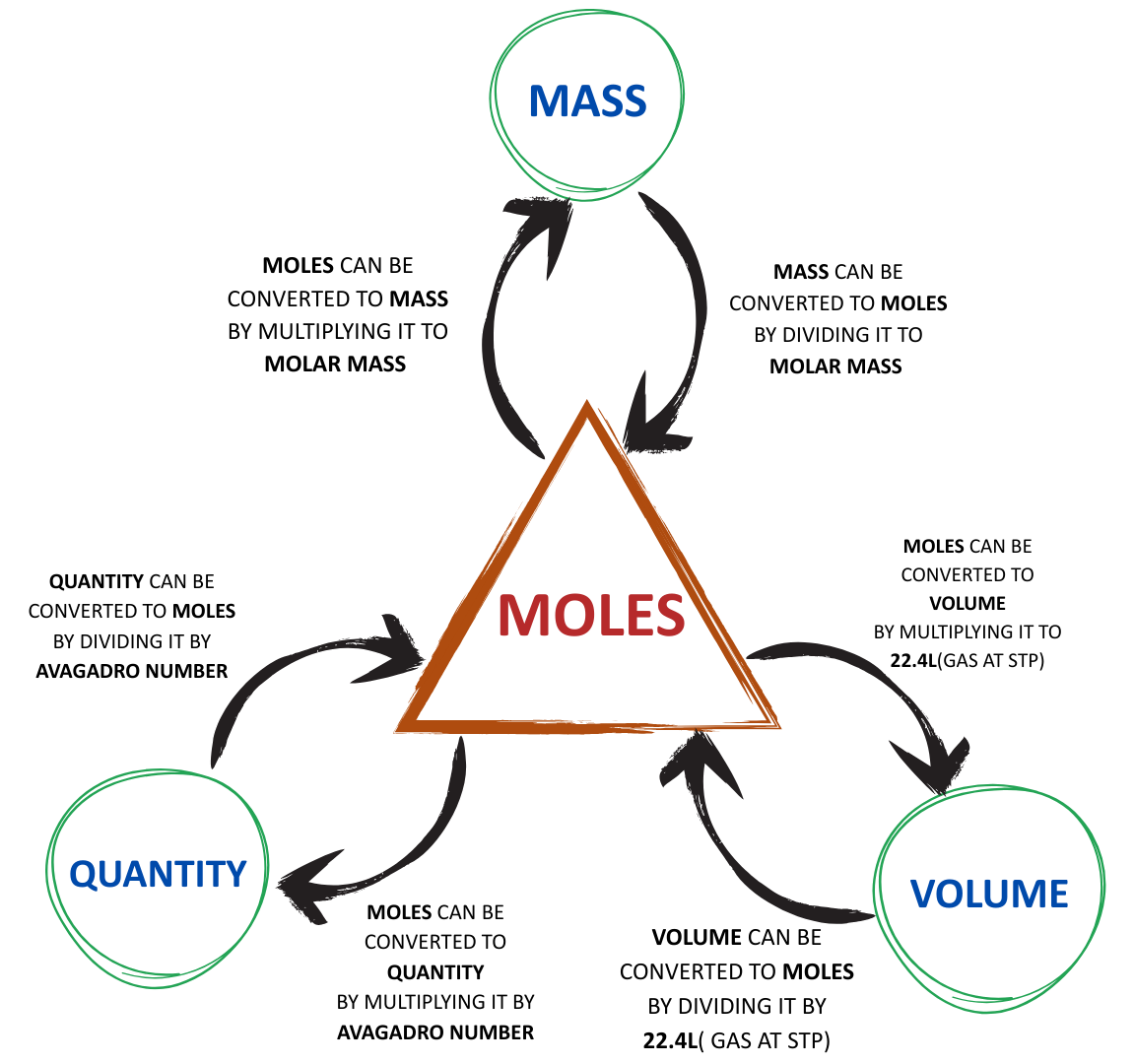

USEFUL CONVERSIONS FOR PROBLEM SOLVING

- NOTE: As a practical idea and in order to make the calculation easy, we can perform these mid steps for the easier solvation of questions.

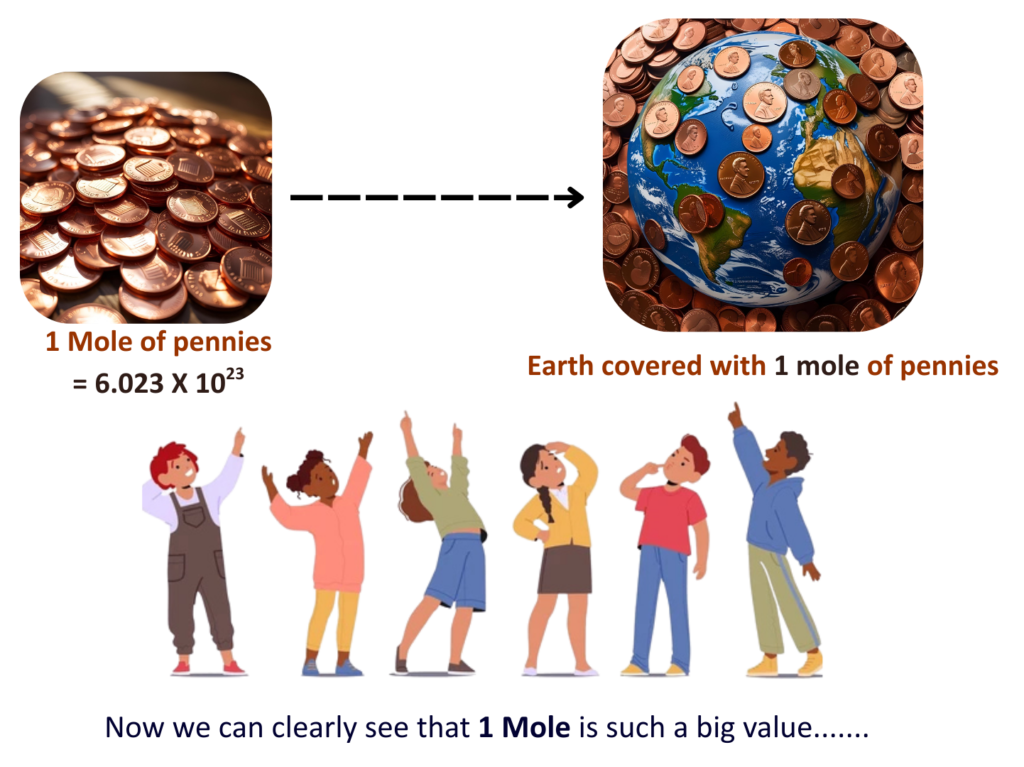

Let us understand it with a fun example:

- Fun Fact: If you had a mole of pennies, you could cover Earth’s surface 5 km deep in coins!

Facts about Mole Concept:

- (1 mole = 6.022 × 10²³ particles (Avogadro’s number)).

- Molar mass = Mass of 1 mole of a substance (in grams).

- Connects microscopic atoms to measurable grams.

- Essential for:

- Balancing chemical equations

- Medicine dosages

- Industrial production

- Environmental science

Solved Example:

Solved Example:

Problem: How many moles are in 36g of water (H₂O)?

Solution:

- Molar mass of H₂O

= (2 × 1) + 16

= 18 g/mol

- Moles = Mass ÷ Molar mass

= 36 g ÷ 18 g/mol

= 2 moles

Final Answer: 2 moles

Solved Example:

Solved Example:

Problem: A recipe uses 8.4 grams of baking soda (NaHCO₃). How many formula units (particles) is this?

Solution:

- Molar mass of NaHCO₃

= 23 (Na) + 1 (H) + 12 (C) + 3 × 16 (O)

= 84 g/mol.

- Moles of NaHCO₃

= 8.4 g / 84 g/mol

= 0.1 moles.

- Number of particles

= 0.1 × 6.022 × 10²³

= 6.022 × 10²² formula units.

Final Answer: 6.022 × 10²²

Solved Example:

Solved Example:

Problem: 1g piece of aluminum foil contains how many aluminum atoms?

Solution:

- Molar mass of Aluminium

= 27 g/mol

- Moles

= 1g ÷ 27g/mol

≈ 0.037 mol

- Atoms

= 0.037 × 6.022 × 10²³

≈ 2.2 × 10²² atoms

Final Answer: 2.2 × 10²² atoms

Relative Formula Mass and Empirical Formula

RELATIVE FORMULA

The relative formula mass (Mᵣ) of a compound is the sum of the relative atomic masses (Aᵣ) of all the atoms in its chemical formula.

- Aᵣ values are found on the periodic table (e.g., C = 12, O = 16, H = 1).

- If an element appears multiple times in a formula, multiply its Aᵣ by the subscript.

Example:

- Water (H₂O)

Mᵣ = (2 × Aᵣ of H) + (1 × Aᵣ of O)

= (2 × 1) + 1

= 18

- Calcium Chloride (CaCl₂)

Mᵣ = (1 × Aᵣ of Ca) + (2 × Aᵣ of Cl)

= 40 + (2 × 35.5)

= 111

Key Applications:

- Stoichiometry: Calculating reactant/product masses in reactions.

- Empirical/Molecular Formulas: Determining compound formulas from mass data.

EMPIRICAL FORMULA

- The empirical formula of a compound shows the simplest whole-number ratio of the atoms of each element present.

Key Points:

- It’s the reduced form of the molecular formula (e.g., C₆H₁₂O₆ → CH₂O).

- Found using experimental data (mass or % composition).

- Does not show the actual number of atoms (unlike molecular formula).

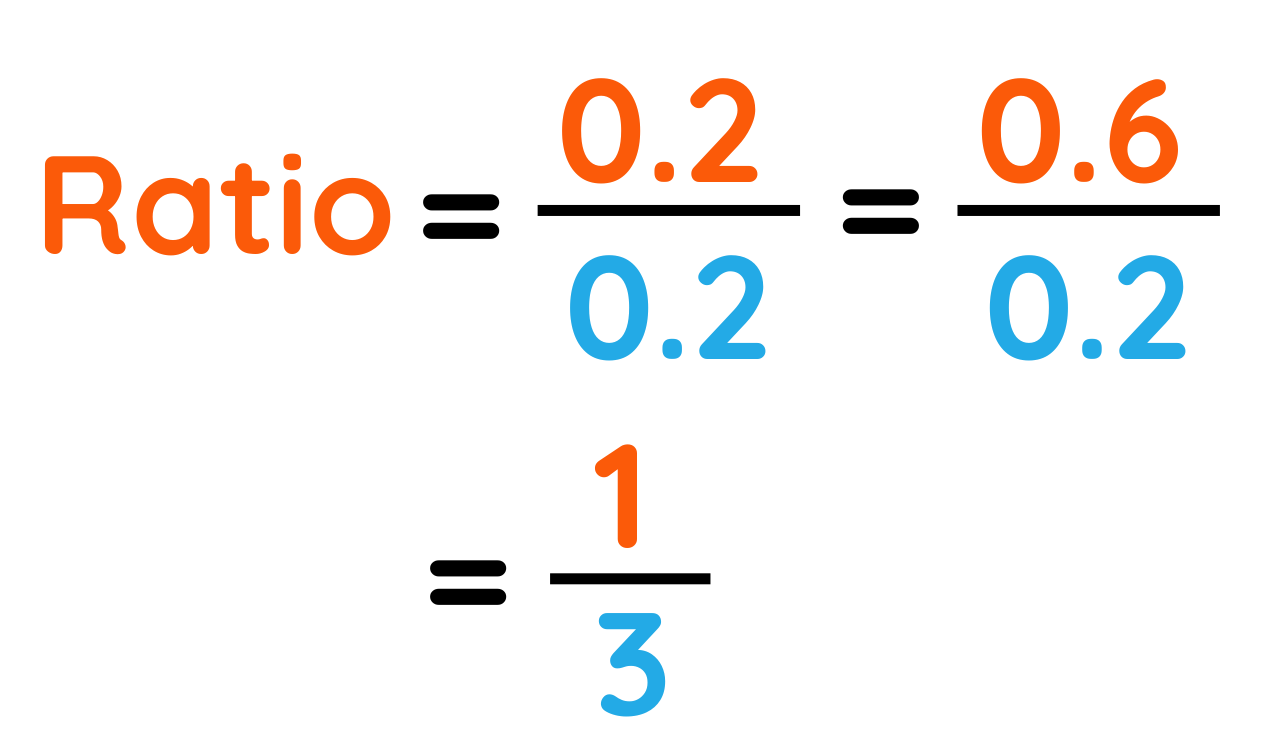

Example:

- A compound has 2.4g Carbon & 0.6g Hydrogen.

- Moles of C

= 2.4 ÷ 12

= 0.2

- Moles of H

= 0.6 ÷ 1

= 0.6

Empirical formula = CH₃

Key Applications:

- Compound Identification – Simplest ratio for unknown substances.

- Molecular Formula Basis – Used with molar mass to find true formula.

- Stoichiometry – Balances reactions & calculates reactant/product masses.

Deduce Molecular Formula from Empirical Formula

Simple Steps:

1. Find the mass of the empirical formula

- Add up the atomic masses of all atoms in the empirical formula.

2. Divide the actual molecular mass by the empirical formula mass

- This gives a multiplier (n).

3. Multiply each atom in the empirical formula by this number (n)

- This gives the true molecular formula.

Example:

- Empirical formula = Fe₂O₃

- Given molecular mass = 400 g/mol

Step #1: Mass of Fe₂O₃

Fe = 56, O = 16

= (2 × 56) + (3 × 16)

= 112 + 48

= 160 g/mol

Step #2: Find multiplier (n)

n = Molecular Mass / Empirical Mass

= 400 / 160

= 2.5

- Since formulas need whole numbers, check for calculation errors or possible non-integer ratios (e.g., if given data is approximate).

Law of Conservation of Mass

- In any chemical reaction, the total mass of the reactants (starting materials) always equals the total mass of the products (what you end up with). No atoms magically appear or disappear—they just rearrange!”

How It Works in Different Situations

1. In a Closed System (Sealed Container)

- Mass stays exactly the same

- Example: Mixing two solutions in a closed flask that forms a solid (precipitate).

- Even though liquids turn into a solid, all atoms are still inside the flask—just in a new form.

2. In an Open System (Unsealed Container)

- Mass can seem to change

- Example: Baking soda + vinegar in an open beaker produces bubbles (CO₂ gas).

- The gas escapes into the air, so if you weigh it, the mass decreases.

- If a reaction absorbs gas (like iron rusting), the mass increases.

Stoichiometry

- Stoichiometry uses mass measurements from experiments to determine the balancing coefficients in chemical equations. The process converts:

Mass (g) → Moles → Simple Ratio → Balanced Equation

- Balancing numbers in a symbol equation can be calculated from the masses of reactants and products:

- convert the masses in grams to amounts in moles (moles = mass/Mr)

- convert the numbers of moles to simple whole number ratios

Example:

For the reaction:

Cu + O2 -> CuO (not balanced),

- 127g Cu react, 32g of oxygen react and 159g of CuO are formed.

- Work out the balanced equation using the masses given:

(Moles = Mass/Molar Mass)

- Cu: moles

= 127/ 63.5

= 2

- O2: moles

= 32 / (16 x 2)

= 32/32

= 1

- CuO moles

= 159 / (16 + 63.5)

= 2

- Therefore you have a ratio of 2 : 1 : 2 for Cu:O2 :CuO, making the overall balanced equation [2Cu + O2 -> 2CuO]

Frequently Asked Questions

Solution:

A mole (mol) is the SI unit for counting particles (atoms, molecules, ions).

- 1 mole = 6.022 × 10²³ particles (Avogadro’s number).

- Analogy: Like a “dozen” (12 items), but for atoms!

Solution:

Steps that must be followed:

- Calculate moles of both reactants.

- Compare to the mole ratio in the balanced equation.

- The reactant that produces fewer moles of product is the limiting reactant.

Solution:

- Law of Conservation of Mass: Atoms are rearranged, not destroyed.

- Exception: In open systems, gases may escape (e.g., CO₂ in baking soda/vinegar reactions).

Solution:

- Relative atomic mass (Aᵣ): Average mass of an atom (unitless, from periodic table).

- Molar mass: Mass of 1 mole of a substance (units: g/mol).

Example: Carbon’s Aᵣ = 12 → Molar mass = 12 g/mol.

Solution:

- Electronic balance (for solids/liquids)

- Gas syringe (for gas volumes → convert to mass using moles)